Sidita holds a Master degree in Human Rights and Multi-level Governance from the University of Padova, with an interdisciplinary focus and action-oriented approach to the study of human rights in a multi-level context.

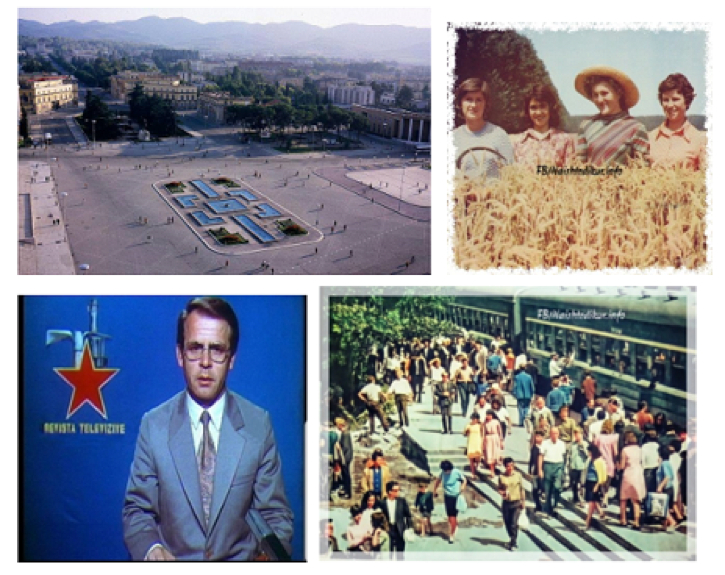

Almost two decades after the fall of the communist regime in Central and Eastern Europe, a growing trend of nostalgic attitudes towards the past emerged in post-communist societies. The common trend of nostalgia observed in eastern Germany (GDR) and among former East Bloc has been referred to as "Ostalgie", a combination of the word "Osten" meaning east and nostalgia.

Nostalgia is a byproduct of society and it is triggered by disillusionment with the present reality. Nostalgic attitudes towards the socialist past are motivated by multiple factors: the disintegration of family bonds, the lack of feeling of belonging, the fading of traditions, societal transformation, mass migration, expansion of consumerism and a growing void resulting from the pursuit of material goods.[1]

The transition from a collectivist society to a capitalist one is associated with the transformation of people's lifestyles, disintegration of social bonds in which previously societies had been embedded, thus giving way to new societies driven by profit, shaped by neo-liberal policies such as privatization and liberalization of trade. The transition to capitalism in Albania, had far-reaching negative consequences such as the demolition of welfare state, the rise of unemployment rate, the emergence of turbo-capitalism[2], and the rise of social injustice, accompanied by a prolonged period of political uncertainty.

In the light of such political and societal change, people long for an era when there was social order and when the individual's fulfilment and moral values were inseparable from society. Thus, nostalgia is an attempt to imbue today's world with the positive aspects of the bygone era. Some of the aspects that people view as positive with regards to the past include a general feeling of security, social stability, regulated employment, free education, free healthcare, state enterprises and state-controlled production, genuine social bonds, healthy lifestyle, among others.

Nostalgia can be examined on the level of individuality – as private memories about the past, and on the level of society – as collective memories about the past. Both private and collective memories of the past are based on selective remembering of positive aspects of the past and forgetting the negative ones.

For example, Lirka, former accountant and member of a former persecuted family highlights the pleasant aspects of the past such as "harmony and geniality between a close circle of family members and friends" while minimizing the negative ones such as "economic hardships and suffering of my family" due to persecution. "Whereas today people have become more distant with each-other and maybe it is so because of capitalism" [3] she concludes.

The Public Memory of Communist past in Public Discourses

The public memory of communist period during the early phases of post-communism in Albania, was a taboo topic in public discourses. The first effort to articulate a public demand to deal with the legacy of the communist past at the national level crystallized in 2010, with the case of the "Pyramid"[4], and it centered around the proposals for the demolition versus the preservation of the building.

Berisha, the right-wing prime minister at the time planned to demolish the former museum and to erect a new "temple of democracy" building for Albania's Assembly while Rama, head of the left-wing party in opposition insisted on preserving the building as evidence of Albania's history and culture.[5]

In 2016, a national survey[6] on Citizens' perceptions of the communist past in Albania, revealed for the first time that Albanians "have very ambivalent feelings about the communist past."[7]

According to the published results, 62% of the respondents felt that the Communist legacy in Albania is "somewhat problematic", while 35% felt that it is "not a problem at all." Economy, Corruption, Education and Environmental Pollution were chosen by respondents, among the ranks that pose "big problems" in comparison to the legacy of the communist past, whereas other ranks such as Order/Security were perceived as less problematic in comparison to the above ranks, but still more problematic than the communist legacy.[8] According to historian Celo Hoxha, "the fact that the communist crimes have still not been condemned produces this kind of result"[9], the tendency to view communism with nostalgic eyes by many people in Albania.

While the legacy of socialism in Albania has been contested, one thing is certain: that socialism gave Albania railways, free healthcare, mass literacy, electricity and universal suffrage, although citizens could vote only for the Communist party. As Lucas, US reporter at Boston Herald, observed during his multiple visits to Albania, after the regime change "many people remarked the time when they had a job, but they had no freedom. Now they had freedom, but they had no jobs." [10]

Indeed, according to the same survey, Albanians cited "Public order", followed by "Job security" and "Good healthcare", as the top positive aspects of the Communist period in Albania. Other positive aspects mentioned included: Education system, social equality, rule of law and minimum standards of living, respectively. Whereas "Lack of freedom", followed by "Class war" and "Violation of Civil and Human Rights" respectively, were mentioned as the three most negative aspects of the regime, according to the same survey. Other negative aspects mentioned included: poverty, inefficiency of food, dictatorship as a political regime, presence of terror feeling, religion & education limitations and the collectivization respectively. [11]

The ubiquitous bunkers are the quintessential example of neo-nostalgia combined with a market conscious attitude that has characterized the new wave of heritagization in Albania.

The last years have seen an increasing interest in appropriation of the bunkers, proper to the consumption of "bunker fantasy" and with interest for the tourism sector. While some of them have been repurposed as café and restaurant, "bed & bunker" and even a tattoo parlor, others have gradually become what Theodor Adorno called "kulturlanschaft"[14], ruined constructions returned to nature. Once constructed as fortification objects for the function of self-defense, today they can be appreciated for their aesthetic and artistic value.

As Çaushi highlighted: "It is important to condemn Enver Hoxha and one way to do so is by converting those structures that he had created to keep people isolated into structures that attract people/custom."

Communist-era movies: "offensive and denigrating" vs. "a cinematic heritage"

On 30 Mach 2017, a proposal requiring the ban on the broadcast of communist-era films from national media, sparked controversy and spurred a public debate on decommunization.

The proponents of the proposal argued that the screening of communist-era movies loaded with propaganda "keeps alive and activates nostalgia for the dictatorship" and "does great damage to public health"[17], particularly to the young generation who are not well-informed about the communist era atrocities due to a gap in school curricula. The propaganda falsifies and distorts historical events, manipulates the truth, glorifies the Labor Party and its leaders and creates moral and national stigma by portraying members of certain groups as dangerous enemies of the country.

On the other hand, the critics of such proposal including many film producers, film critics and actors who starred in the communist-era films, shared a concern that banning those movies from television screens would result in an almost complete erasure of Albania's cinematic heritage.[18]

Kolec Traboini, a screenwriter for the KinoStudio during the communist era, considered the proposal inacceptable as "it is one thing to hate communism, and another is to know the realities of the time."[19] For Mark Cousins, director, film critic and advisor at the Albanian Cinema Project, banning the communist films would be a counter-productive way to deal with the wounds of the past as "Films didn't commit the crimes of the Hoxha era" and "they are not better or worse than their times" but "they are evidence of what was thought and felt."[20]

For the broader audience, the good acting, authentic movie characters and memorable communist-era film quotes evoke memories of a familiar sight of childhood in the days gone by.

Afterall, the proposal did not receive enough support from the public and at present, there are no laws in place to regulate the broadcast of communist-era cinematographic production in national media.

A Contested Collective Memory: The fine line between remembrance and appropriation of communist symbolism

The inauguration of Bunk'Art in 2014, a communist-era underground bunker transformed into a museum dedicated mainly to communist memory at a time when the nation's communist memory was still contested, sparked public debates and accusations of the project being politically motivated. In addition, the fact that the government who was responsible for the realization of Bunk'Art was a socialist one[21], has been criticized as, among other things, an attempt to appropriate the symbolism of the communist regime.[22]

Bollino, curator of Bunk'Art and Bunk'Art 2, explains that alongside the technical difficulties of recovering communist-era documents, "the greatest difficulties were cultural: […] as he "struggled a lot to make it clear that remembering the facts of the communist period does not mean having nostalgia for communism."[23]

The cultural difficulties intensified further with the inauguration Bunk'Art 2 museum in 2016, which was not well-received by the public and became subject to controversy.[24]

The designation of the entrance in the form of an artificial igloo-shaped bunker, similar to those constructed during Hoxha's regime and its location in a central public space without prior public consultation, caused public reactions which eventually led to a protest. The protest was fueled by accusations of the right-wing party against the left-wing party in power, for being insensitive towards the former persecuted people or families of victims who suffered under the communist regime, alongside accusations for evoking nostalgia for the dictatorial regime.

Eventually, the protest of December 2015 degenerated into vandalism and the fake bunker was set on fire and was defaced by angry protestors. The holes that remained in the external walls of the bunker were covered in transparent plastic and repurposed as windows, thus ironically commemorating the intense public reactions against it. The museum has already been accepted by the population now.

For Elton Caushi, co-founder of Albanian trip "the entrance-bunker was an eccentric choice. The damage that was done to it was intentionally covered with plastic to show a part of Albania's contemporary history too, to make the discussions about the bunkers relevant."

Regardless of the ambivalent feelings towards the communist regime and the contested collective memory in Albania, the results of the national survey[25] show that nearly 77% of the respondents support the creation of a museum about the communist regime whereas 63% think that the communist-era sites of persecution should be preserved for future generations.

Nostalgia: "A Necessary Evil"

All in all, nostalgia is a complex emotion and should not be equated or reduced to an irrational desire to restore the past, as it has been broadly misperceived. It should be treated as part o