Full article has been published by Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy (CYELP) DOI: 10.3935/cyelp.17.2021.455 (https://www.cyelp.com/index.php/cyelp/article/view/455).

The EU is not only a 'Community based on the rule of law' but it is a Community/Union based solely or at least primarily on the rule of law.[1] The rule of law is enshrined at the core of European Union primary law − it is listed among the founding values of the Union and is stated as an objective that determines the way in which the EU exercises its competencies.[2] Likewise, it is also recognised as a value defining EU membership, given Article 49 TEU which stipulates that every European state that respects the values referred to in Article 2 (basic values of the EU) and is committed to their promotion may apply to become a member of the EU. Hence, the enlargement of the Union is based on achieving and respecting certain values: the fundamental values of the EU including the rule of law.

Since the rule of law was introduced into the EU enlargement policy, its role within the conditionality policy has advanced gradually so that it has become the cornerstone of the accession process. In this short overview of the EU rule of law promotion within the enlargement policy, we will strive to identify what are the main challenges in this regard and the main reasons why the EU has made the rule of law central to its new enlargement methodology.

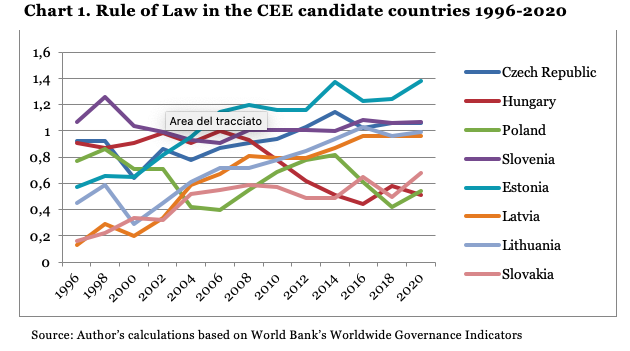

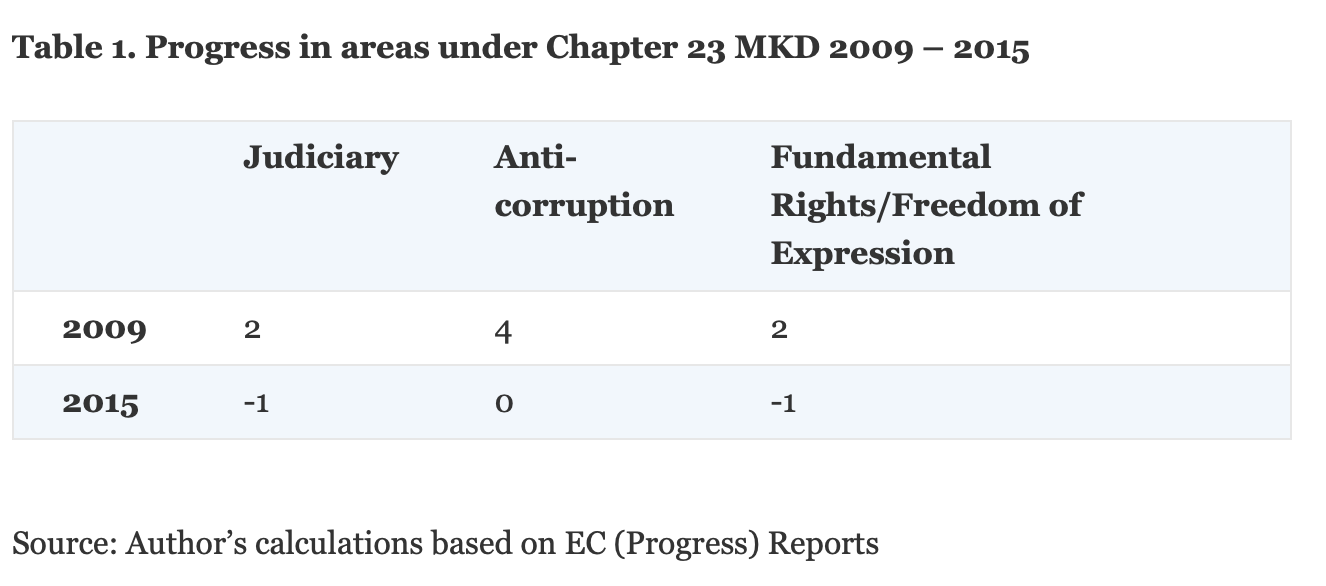

Although the rule of law was included in the Copenhagen criteria and the Amsterdam principles, the approach in the EU accession of the Central and Eastern European states (CEE) focused mainly on the legal transposition of the EU acquis and institution building − the necessary administrative and judicial structures for the correct application of EU legislation, whereby the rule of law was not touched upon in its substance. Due to the limited scope of the EU acquis in many of these areas covered by the Copenhagen criteria, mainly the rule of law, the missing normative content was filled by referring to the European standards developed by other regional/international organisations such as the Council of Europe rules or OSCE principles. The main elements of the EU-driven reforms referred to the intensified alignment of domestic legislation with European and international standards, including approximation with the acquis communautaire, as well as increased legislative output that potentially weakened legal stability.[3]

Even so, this approach brought difficulties on how to measure progress and was criticised for its rather 'simplistic sum'[4] of the rule of law and democracy and the lack of 'actual substance'.[5] In this manner, there was a discrepancy between the accession conditions and membership obligations because the norms the Union has promoted in the context of enlargement go well beyond the perimeter of the EU acquis stricto sensu.[6] Lack of a uniform conception of the rule of law affected how applicant countries reform their governmental structures according to their interpretation of the concept and had the potential of influencing and disrupting the further expansion of the EU to include countries from CEE.[7] Therefore, the rule of law is part of the so-called 'enlargement acquis' within the EU's accession conditionality but not, or only to a limited extent, part of the EU acquis.[8]

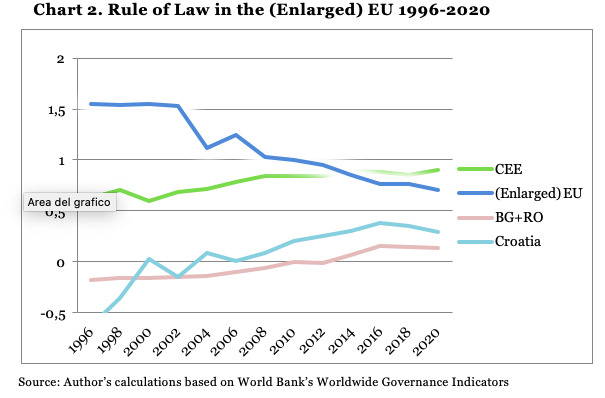

The extension of EU membership to CEE has been a process of fundamental domestic change in response to EU rules and regulations but (some of) the states that entered the EU from 2004 onwards did not finish the transformation process on the date of accession. In these areas the EU often gave 'priority to efficiency over legitimacy'[9] regardless of the conditionality policy. Moreover, it became apparent that the Europeanisation process may even be reversible and revealed stagnating and even declining trends, where the rule of law had not improved significantly and had even further deteriorated, thus questioning the EU transformative power. The decision to allow the accession of 'imperfect' new Member States did not follow consistently the ratio behind the conditionality policy but represented primarily a political decision driven by 'wider security imperatives' to some extent.[10] Hence, the identified problems and inconsistencies pointed to 'the gap between conditionality on paper and conditionality in practice',[11] suggesting that 'conditionality can only become a true principle of enlargement, when the whole accession process is mostly moved away from the sphere of politics into the realm of the law'.[12]

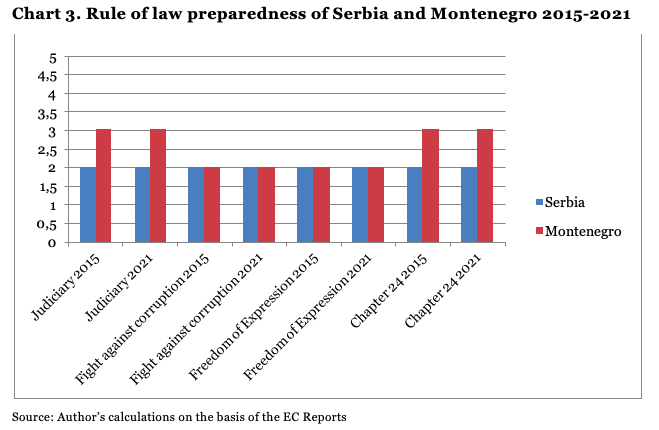

In February 2018, the European Commission reaffirmed the firm, merit-based prospect of EU membership for the Western Balkans by adopting the 'Credible Enlargement Perspective for an Enhanced EU Engagement with the Western Balkans' Strategy,[19] which came almost fifteen years after the last EU-Western Balkans Summit in Thessaloniki in 2003, perceiving the Western Balkans enlargement process as a geostrategic investment for the Union. The underlying message in the rule of law initiative is that the Commission plans to make use of all of the leverage provided in the accession talks frameworks for as long as possible, by delaying the Western Balkans accession to the EU in order to avoid any repetition of the scenarios of Hungary and Poland[20] or when observing clear elements of backsliding in the membership commitments to the rule of law[21] and persisting problems with organised crime as in the case of Bulgaria. Still, this new Strategy was not enough to overcome the impasse in the EU's enlargement policy on the Western Balkans that has been running on 'autopilot' for the last fifteen years,[22] thus in March 2020 the EU once again − or more precisely for the fourth time − formally[23] introduced new rules on accession negotiations by adopting the new Enlargement Methodology on the basis of the Commission's proposal entitled 'Enhancing the accession process: A credible EU perspective for the Western Balkans'.[24]

In February 2018, the European Commission reaffirmed the firm, merit-based prospect of EU membership for the Western Balkans by adopting the 'Credible Enlargement Perspective for an Enhanced EU Engagement with the Western Balkans' Strategy,[19] which came almost fifteen years after the last EU-Western Balkans Summit in Thessaloniki in 2003, perceiving the Western Balkans enlargement process as a geostrategic investment for the Union. The underlying message in the rule of law initiative is that the Commission plans to make use of all of the leverage provided in the accession talks frameworks for as long as possible, by delaying the Western Balkans accession to the EU in order to avoid any repetition of the scenarios of Hungary and Poland[20] or when observing clear elements of backsliding in the membership commitments to the rule of law[21] and persisting problems with organised crime as in the case of Bulgaria. Still, this new Strategy was not enough to overcome the impasse in the EU's enlargement policy on the Western Balkans that has been running on 'autopilot' for the last fifteen years,[22] thus in March 2020 the EU once again − or more precisely for the fourth time − formally[23] introduced new rules on accession negotiations by adopting the new Enlargement Methodology on the basis of the Commission's proposal entitled 'Enhancing the accession process: A credible EU perspective for the Western Balkans'.[24]

Hence, even if incentives are strong in principle, they fail to affect rule adoption and compliance if they lack credibility.According to the new Enlargement Methodology, more credibility is indicated as the first condition for reinvigorating the accession process to deliver its full potential, but it is emphasised that 'it needs to rest on solid trust, mutual confidence and clear commitments on both sides'.[32] The EU should particularly discourage bilateral issues from dominating the enlargement agenda. On the one hand, because they undermine the merit-based prospect of full EU membership and its main principles − predictability and conditionality, the mutual trust and confidence necessary for the accession process to be able to deliver its potential, while, on the other hand, having in mind the Western Balkans landscape, these issues have the potential to create serious instability which may be forestalled only by strict rule of law conditionality that will place the focus on the real problems of these societies.

Hence, even if incentives are strong in principle, they fail to affect rule adoption and compliance if they lack credibility.According to the new Enlargement Methodology, more credibility is indicated as the first condition for reinvigorating the accession process to deliver its full potential, but it is emphasised that 'it needs to rest on solid trust, mutual confidence and clear commitments on both sides'.[32] The EU should particularly discourage bilateral issues from dominating the enlargement agenda. On the one hand, because they undermine the merit-based prospect of full EU membership and its main principles − predictability and conditionality, the mutual trust and confidence necessary for the accession process to be able to deliver its potential, while, on the other hand, having in mind the Western Balkans landscape, these issues have the potential to create serious instability which may be forestalled only by strict rule of law conditionality that will place the focus on the real problems of these societies.

To overcome the absorption capacity issue and enlargement impasse, the EU must explore all avenues for the advanced integration of the Western Balkans in the period preceding accession in line with its commitments for phased-in accession as defined in the new methodology while maintaining the central role of rule of law conditionality. Finally, there is clear and close interrelation of the internal and external dimension of the rule of law − its protection within the Union and the ability to deal with internal backsliding on the one hand, and the promotion of the rule of law in the enlargement policy and the projection of this core EU value beyond, on the other. This in turn will strengthen the Union on the inside by reinforcing the EU role as a global player.

[1] Frank Emmert, 'Rule of Law in Central and Eastern Europe', (2008) 32(2) Fordham International Law Journal 551, 582.

[2] Cristophe Hillion, 'Overseeing the rule of law in the European Union: Legal mandate and means' [2016] European Policy Analysis 1.

[3] Martin Mendelski, The EU's Rule of Law Promotion in Central and Eastern Europe: Where and Why Does It Fail, and What Can be Done About It? (Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law 2016) 5.

[4] Allan Tatham, Enlargement of the European Union (Kluwer Law International 2009) 209.

[5] Päivi Leino, 'Rights, Rules and Democracy in the EU Enlargement Process: Between Universalism and Identity' (2002) 7 Austrian Review of International and European Law 53, 80.

[6] Christophe Hillion, 'EU Enlargement' in Paul Craig and Grainne de Búrca (eds), The Evolution of EU Law (2nd edn, OUP 2018).

[7] Dale Mineshima, 'The Rule of Law and the Eastern Enlargement of the EU' (Ph.D. thesis, Old Elvet Durham University 2001) 109 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3827/ accessed 05 June 2021.

[8] Tomasz P.Woźniakowski, Frank Schimmelfennig and Michal Matlak, 'Europeanization Revisited: An Introduction' in Tomasz P.Woźniakowski, Frank Schimmelfennig and Michal Matlak (eds.), Europeanization Revisited: Central And Eastern Europe In The European Union (European University Institute and Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, 2018) 6, 11.

[9] Heather Grabbe, The EU's transformative power. Europeanization through conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) 205.

[10] Dimitris Papadimitriou and Eli Gateva, 'Between Enlargement-led Europeanisation and Balkan Exceptionalism: an appraisal of Bulgaria's and Romania's entry into the European Union' (2009) 10(2) Perspectives on European Politics and Society 152, 164.

[11] Dimtiry Kochenov, EU Enlargement and the Failure of Conditionality: Pre-accession Conditionality in the Fields of Democracy and the Rule of Law (Kluwer Law International 2008) 311.

[12] Ibid, 312.

[13] Hillion (n 6) 193.

[14] Commission, 'The Western Balkans and European Integration' (Communication) COM (2003) 285.

[15] European Council, 'Presidency Conclusions', Brussels, 15 December 2006.

[16] Amichai Magen, 'Cracks in the Foundations: Understanding the Great Rule of Law Debate in the EU' (2016) 54(5) Journal of Common Market Studies 1050.

[17] According to the EU's Enlargement Strategy 2011/2012 developed by the European Commission which lists the areas included in the rule of law concept.

[18] Commission, 'Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2011−2012' (Communication) COM(2011) 666.

[19] Commission, 'Communication on a Credible Enlargement Perspective for and Enhanced EU Engagement with the Western Balkans' COM (2018) 65.

[20] Heather Grabbe and Stefan Lehne, 'Defending EU Values in Poland and Hungary' (Carnegie Europe 2020) https://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/09/04/defending-eu-values-in-po-land-and-hungary-pub-72988 accessed 23 July 2021.

[21] Dariusz Adamski, 'The Social Contract of Democratic Backsliding in the 'New EU Countries' (2019) 56(3) Common Market Law Review 623.

[22] Marko KmeziÊ, The Western Balkans and EU Enlargement: Lessons Learned, Ways Forward and Prospects Ahead, (European Parliament 2015) 6 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/534999/EXPO_IDA(2015)534999_EN.pdf accessed 22 July 2021.

[23] With the Copenhagen criteria as a starting point, Chapter 23 as the second innovation, and the new approach as the third novelty.

[24] Commission, 'A Credible EU Perspective for the Western Balkans' (Communication) COM (2020) 57.

[25] According to the published conclusions from the European Council meeting on 17 and 18 October 2019, the European Council will revisit the issue of enlargement before the EU-Western Balkans-summit planned for May 2020 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41123/17-18-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf accessed 29 July 2021.

[26] Andi Hoxhaj, 'The EU Rule of Law Initiative Towards the Western Balkans' (2021) 13 Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 143, 148.

[27] An analysis of the public discourse on this decision leads to the conclusion that France was the main opponent. In an interview with The Economist published on 7 November 2019, President of France Emmanuel Macron said: 'We can't make it work with 27 of us (…). Do you think it will work better if there are 30 or 32 of us? And they tell me: "If we start talks now, it will be in ten or 15 years". That's not being honest with our citizens or with those countries. I've said to them: "Look at banking union". The crisis in 2008 with these big decisions; end of banking union in 2028. It's taking us 20 years to reform. So even if we open these negotiations now, we still won't have reformed our union if we carry on at today's pace'. The Economist, 'Emanuel Macron in His Own Words' The Economist (London 7 November 2019) https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/emmanuel-macron-in-his-own-words-english?utm_medium=cpc.adword.pd&utm_source=google&ppccampaignID=18151738051&ppcadID=&utm_campaign=a.22brand_pmax&utm_content=conversion.direct-response.anonymous&gclid=CjwKCAjwyeujBhA5EiwA5WD7_ZEgHkonjIHAKW3vbXCb7nvk6k0OC2wHNOGUnQszQJv0S0WWziP-pxoCRtsQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds accessed 28 July 2021. Rym Momtaz and Andrew Gray, 'Macron Urg-es Reform of 'Bizarre' System for EU hopefuls' Politico (Toulouse 16 October 2016) https://www.politico.eu/article/macron-urges-reform-of-bizarre-system-for-eu-hopefuls/ accessed 29 July 2021.

[28] Council of the European Union, 'General Affairs Council conclusions', Brussels, 25 March 2020.

[29] Stabilisation and Association Agreement between the European Communities and their Member States, of the one part, and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, of the other part [2004] OJ L84/13.

[30] Frank Schimmelfennig and Ulrich Sedelmeier, 'The Europeanization of Eastern Europe: The External Incentives Model' (JMF@25 conference, EUI, 22-23 June 2017).

[31] Agreement – Final Agreement for the Settlement of the Differences as Described in the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 817 (1993) and 845 (1993), the Termination of the Interim Accord of 1995, and the Establishment of a Strategic Partnership between the Parties https://vlada.mk/sites/default/files/dokumenti/spogodba-en.pdf accessed 28 November 2021.

[32] Commission (n 24) 2.