Two winners, many losers

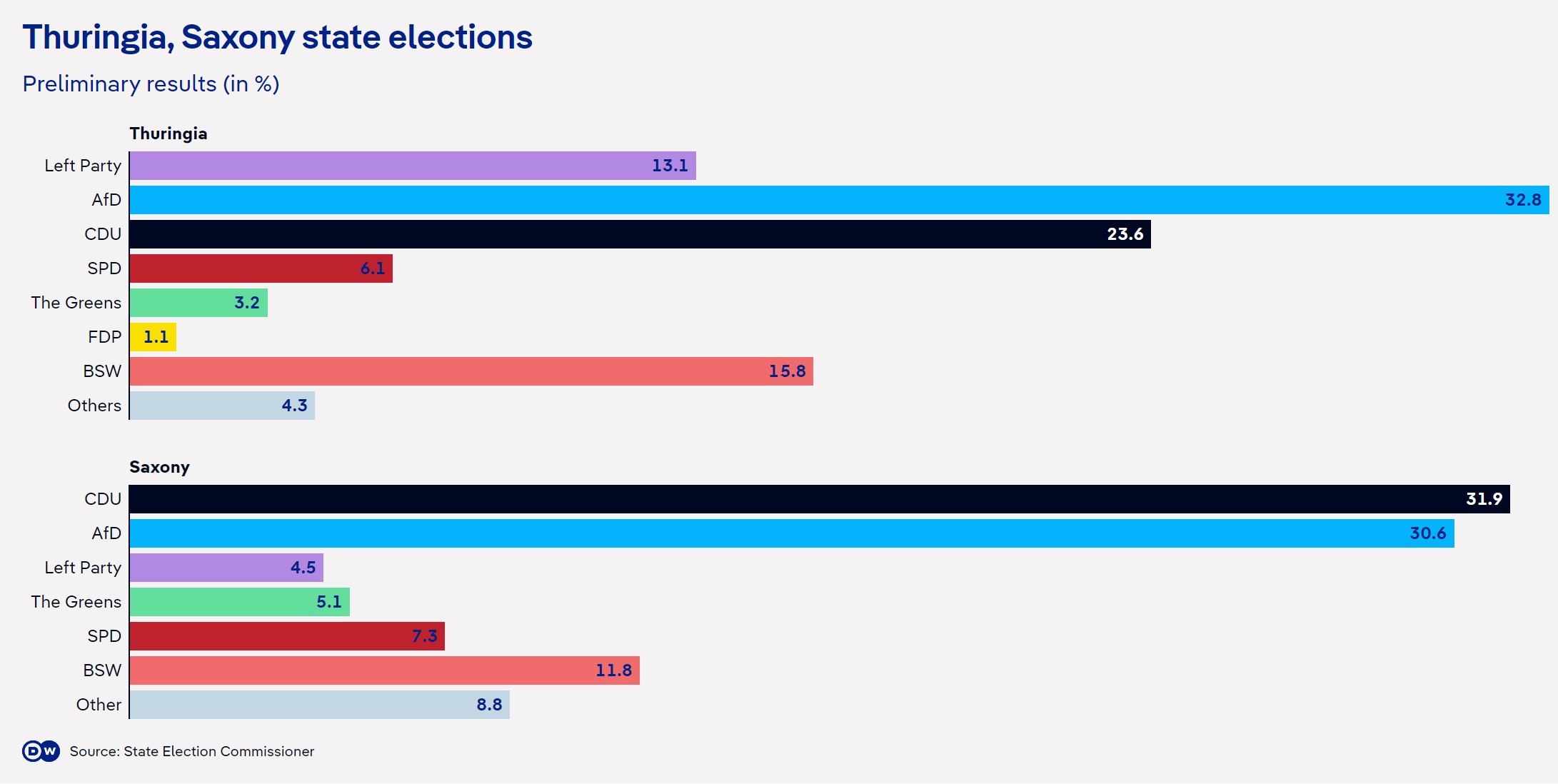

As off the morning of September 2nd, the AfD has obtained more than 30% in both elections. In Saxony, the CDU narrowly managed to overcome them, gaining one more seat in the state parliament. In Thuringia, the AfD has not just become the strongest party, but has also managed to reach 1/3 of the seats in parliament, whereas the CDU has around 23.6%.

The role of the protest party has arguably been taken over by another party. In both elections, the third-biggest vote share was obtained by "Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht" (BSW), where "Bündnis" can be translated to "Alliance". The party, founded by the eponymous German politician in January 2024, split off from "Die Linke" (The Left). The BSW, in a nutshell, combines left-wing economic policy with right-wing positions on migration and LGBTQ+ rights. It also has a notably Russia-friendly foreign policy, demanding an end to support for Ukraine's war effort and no stationing of US long-range weapons in Germany. The astonishing results for a newly founded party can be explained by Wagenknecht's enormously high name-recognition. She has been a well-known face on Germany's political far-left for a long time and is popular for her frank – some would say provocative - mannerisms. The BSW's voters came, logically, mostly from Die Linke but they also managed to mobilise a significant share of non-voters.

Chancellor Scholz's "traffic light coalition" of the SPD, the Greens and the FDP has suffered a harsh defeat. The chancellor called the results "bitter" but also pointed out that the SPD had done better than polled – they had at one point been predicted to fall below the 5% threshold. His coalition partners fared worse, with the Greens not making the 5% threshold in Thuringia and the FDP entering neither state parliament. Coalition infighting, which has been growing increasingly bitter over the past months as the budget was being negotiated, may increase further. The coalition now lacks political representation in two eastern states.

Now what?

Coalition-building will be challenging, to say the least. The CDU has had a long-standing "Unvereinbarkeitsbeschluss", an official decision of incompatibility, against Die Linke. All parties, including the BSW, have said that they will not work with the AfD. At the same time, the BSW has said that they will only enter a coalition that speaks up against the supply of arms to Ukraine and the stationing of US intermediate-range missiles in Germany. Neither of those are competences of the Bundesländer – so it will be interesting to see to what extent this remains a hard line in negotiations.

In Thuringia, a possible majority would be CDU, BSW, and Die Linke, leaving AfD and SPD in opposition. If the CDU refuses to form a coalition with Die Linke, a minority government with their support might be formed. However, Thuringia is emerging from 4-years of minority government. Even though the government has held up for the entire legislative period, none of the involved parties seem interested in repeating the experiment. In Saxony, there are more possibilities – a coalition of CDU, SPD, Greens, the Free Voters – who have one seat – could pair up either with the BSW or with Die Linke to achieve a majority without the AfD.

It is obvious that the main issue binding these coalitions together would be the commitment of keeping the AfD out of government. Beyond that, the political differences are enormous – not just on foreign policy, but also on questions such as the abolition of the constitutional debt-break, the introduction of new taxes, and, of course, migration.

What this means for the government (and Germany)

The AfD is unlikely to govern – for now. If the coalitions that emerge from these elections do not manage to introduce meaningful policies, and instead spend their time infighting, approval for the AfD might increase further the next time around. After all, they will be able to portray themselves as the only opposition party. A similar situation on the national level in Italy, when all parties except Meloni's Fratelli d'Italia entered a coalition government under Mario Draghi, boosted Meloni's support and contributed to her rise to the premiership.

Just because they are not in power does not mean that the AfD will have nothing to do. In Thuringia, they have reached 1/3 of the seats in parliament, and therefore have a so-called "Sperrminorität", a "blocking minority". Any decision requiring a 2/3rds majority can be stopped. This does not just include constitutional amendments, but also the nomination of committee members that then elect justices and public prosecutors. In the case of Thuringia, this majority is also required to elect the commission which acts as the parliamentary control over the domestic intelligence services. Orban's Fidesz party had such a blocking minority between 2002 and 2010 and used it to effectively to sabotage the government's workings.

There are around 4.9 million people eligible to vote in Saxony and Thuringia – circa 8% of Germany's 60 million voters. For scale, Germany's most populous Bundesland, North-Rhine-Westphalia, has 12.8 million eligible voters. Voting behaviour in Germany's eastern states also needs to be analysed in light of its historical context and the demographic and economic conditions there. Hence, these elections cannot be used as reliable predictors for politics on the federal level, or next year's general election. Then again, the traffic light coalition's abysmal electoral performance is unlikely to better the already tense mood in Berlin. Current polls are showing the AfD between 16 and 20 percent across Germany. Thuringia, Saxony, and possibly Brandenburg, will therefore serve as testing grounds. Will the AfD manage to use the blocking minority in Thuringia effectively to increase support? Will the other parties overcome differences to form coalitions? Will some of them – for example the right-wing of the CDU in Thuringia – give in, and work with the AfD? What kind of policies can we expect from the BSW?

Achieving stable, productive governance in Thuringia and Saxony is going to be difficult. Yet it is a necessary condition to stop the AfD's vote share from keeping on rising.